Knee osteoarthritis (OA), also known as degenerative joint disease of the knee, is typically the result of wear and tear and progressive loss of articular cartilage. It is most common in the elderly. Knee osteoarthritis can be divided into two types, primary and secondary. Primary osteoarthritis is articular degeneration without any apparent underlying reason. Secondary osteoarthritis is the consequence of either an abnormal concentration of force across the joint as with post traumatic causes or abnormal articular cartilage, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Symptoms

Pain:

Deep ache in the groin that can radiate to the thigh, or back of knee. It may worsen with activity or at night.

Stiffness:

Particularly noticeable in the morning or after rest, which may improve after an hour or so of movement.

Reduced mobility:

Difficulty with activities like walking, bending, putting on shoes, or getting in and out of a car.

Other sensations:

A “locking” or cracking feeling in the joint is fairly common.

Management

Self-management:

Weight management: Losing weight can significantly reduce the strain on the hip joint.

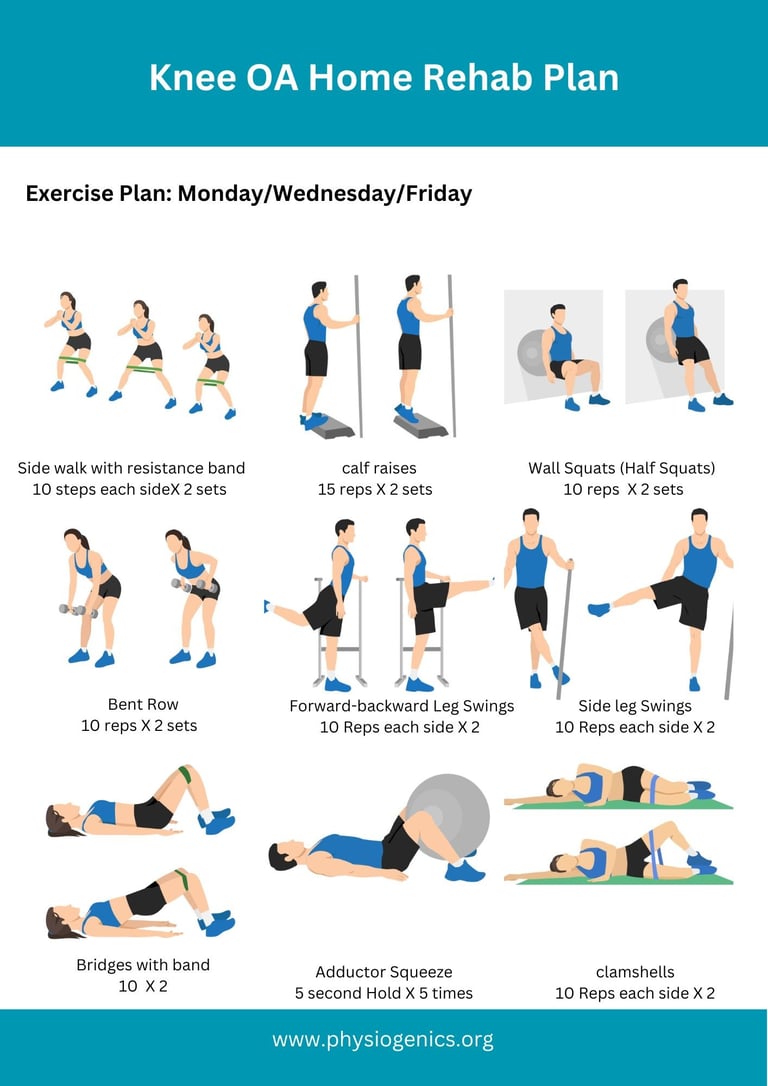

Exercise: Regular, low-impact aerobic exercises like walking, cycling, or swimming, as well as strengthening exercises, can help manage pain and improve function.

Activity pacing: Avoid sitting for long periods and try to avoid activities that cause excessive pain.

Positioning: Use cushions to raise the height of chairs to make getting up easier. When sleeping, a pillow between the knees while on your side can help maintain a neutral position.

Risk Factors for Knee Arthritis

Age. The older you are, the more likely you have worn out the cartilage in your knee joint.

Excess weight. Being overweight or obese puts additional stress on the knees.

Injury. Severe injury, such as a knee fracture or cartilage/meniscus tears, can cause arthritis years later.

Overuse. Jobs and sports that require physically repetitive motions that place stress on the knee can increase risk for developing osteoarthritis.

Gender. Women who are postmenopausal are more likely to develop knee osteoarthritis than men. Rheumatoid arthritis affects women more than men.

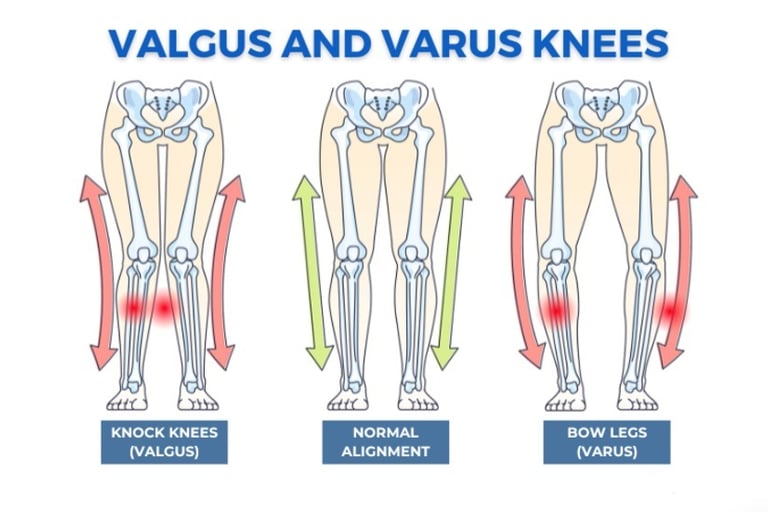

Structural or developmental abnormalities. Irregularly shaped bones forming the knee joint, such as increased Q angle (Knee valgus/varus) , can lead to abnormal stress on the cartilage.

Autoimmune triggers. While the causes of rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis remain unknown, triggers of autoimmune diseases are an area of active investigation. For example, infection is believed to be one of the triggers for psoriasis.

Genetics. Certain autoimmune conditions that lead to knee arthritis may run in the family.

Other health conditions. People with diabetes, high cholesterol, hemochromatosis (high levels of iron in the blood) and vitamin D deficiency are more likely to develop osteoarthritis.

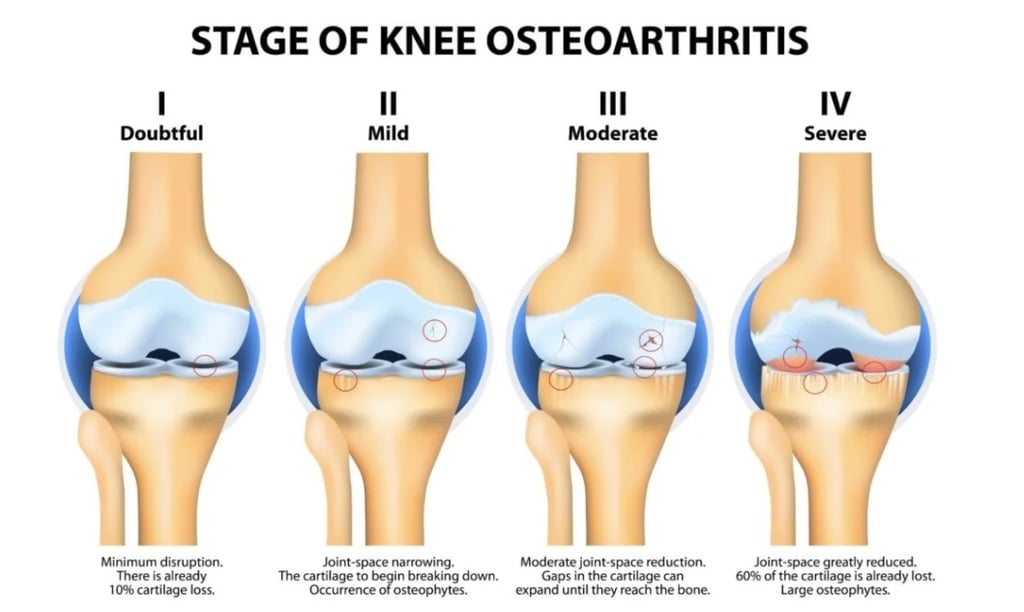

Stages of OA knee:

Grade 1: Very minor bone spur growth and is not experiencing any pain or discomfort.

Grade 2: This is the stage where people will experience symptoms for the first time. They will have pain after a long day of walking and will sense a greater stiffness in the joint. It is a mild stage of the condition, but X-rays will already reveal greater bone spur growth. The cartilage will likely remain at a healthy size.

Grade 3: Moderate OA. Frequent pain during movement, joint stiffness will also be more present, especially after sitting for long periods and in the morning. The cartilage between the bones shows obvious damage, and the space between the bones is getting smaller.

Grade 4: This is the most severe stage of OA. The joint space between the bones will be dramatically reduced, the cartilage will almost be completely gone and the synovial fluid will be decreased. This stage is normally associated with high levels pain and discomfort during walking or moving the joint.

Osteoarthritis knee management:

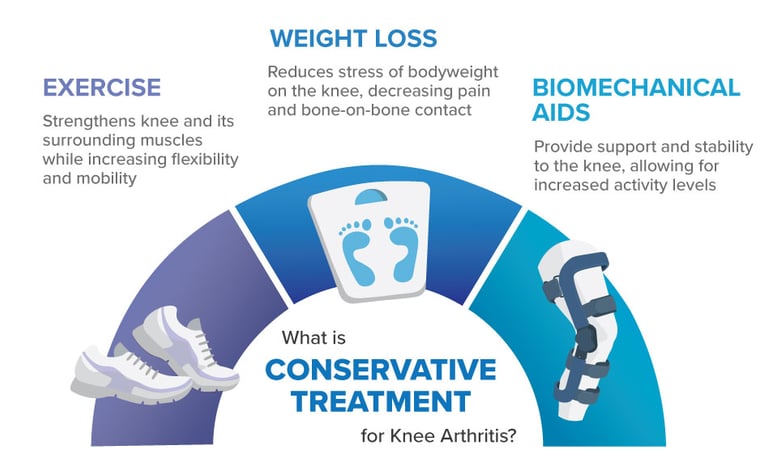

I. Conservative management: The primary treatment for OA knee conservatively is through exercises and physiotherapy.

Exercise therapy

Activity modification

Advice on weight management: BMI around 25.

Knee bracing: in obvious cases of varus or valgus deformity

II. Pharmacological management:

Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) for knee osteoarthritis.

Consider oral NSAID (Ibuprofen/Naproxen) if topical medicines are ineffective or unsuitable along with gastroprotective treatment.

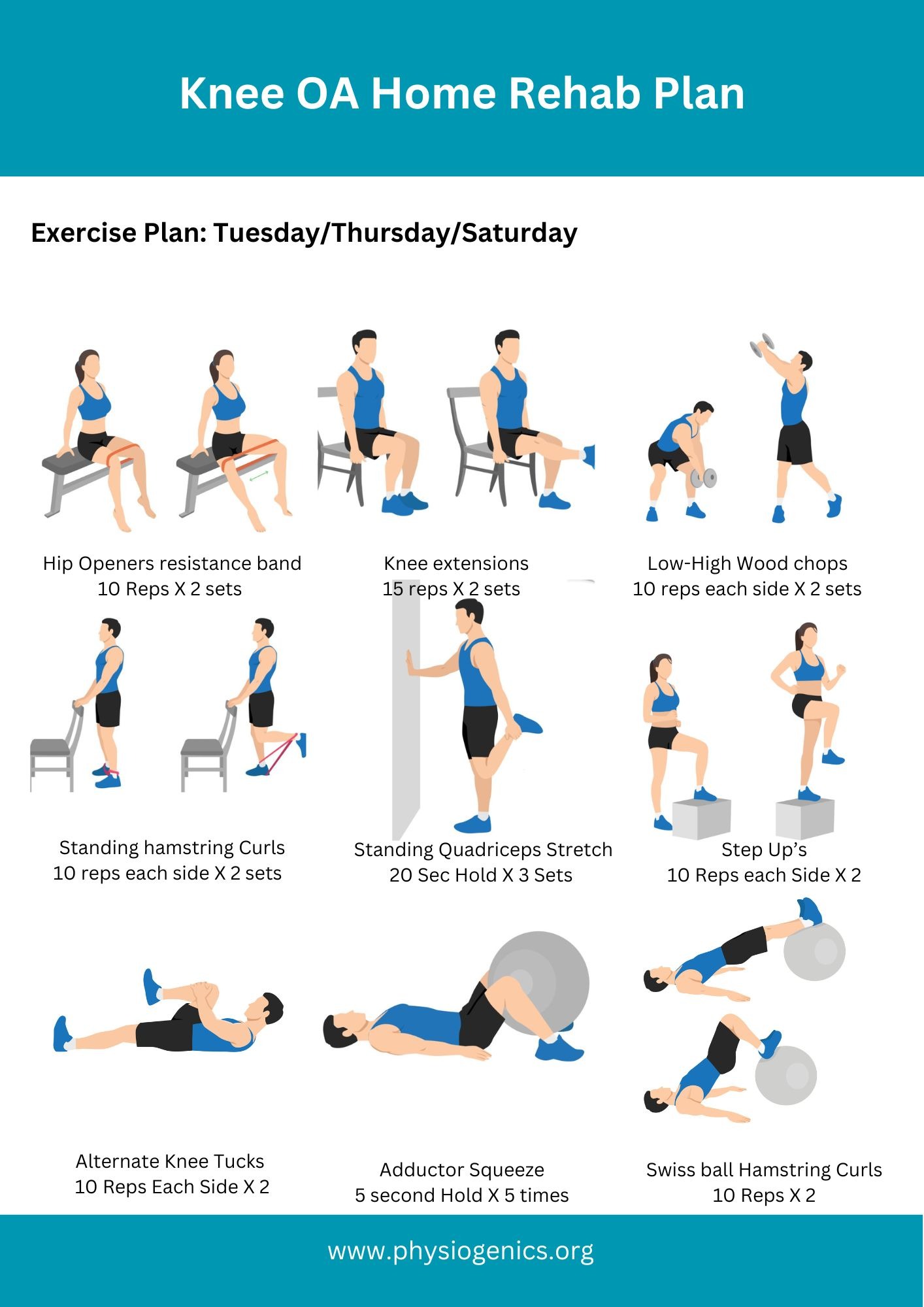

Home Exercise Plan: Beginner

Corticosteroid Injections or Hyaluronic Acid Injections

Corticosteroid (cortisone) injections offer fast, short-term pain relief by reducing inflammation, ideal for acute flare-ups, while Hyaluronic Acid (HA) injections provide longer-lasting lubrication and cushioning, better for managing moderate osteoarthritis symptoms over months, though often taking longer to work; steroids are powerful but have risks with frequent use, whereas HA is generally safer but might need repeated treatments. Your choice depends on needing quick relief versus sustained comfort, and your doctor’s recommendation considering severity and history.

Corticosteroid Injections (Cortisone)

Pros: Rapid pain relief (within days), potent anti-inflammatory.

Cons: Relief is temporary (weeks to months); frequent use can potentially harm cartilage cells.

Best For: Sudden, severe inflammation or pain flare-ups.

Hyaluronic Acid (HA) Injections

Pros: Lubricates and cushions the joint, longer-lasting relief (months), lower risk of joint damage.

Cons: Takes longer to work; effects may vary.

Best For: Mild to moderate osteoarthritis, providing a protective effect.

Key Differences & Considerations

Speed vs. Duration: Steroids are fast; HA lasts longer.

Mechanism: Steroids fight inflammation; HA lubricates and protects.

Safety: HA generally has fewer side effects and doesn’t damage cartilage like frequent steroids might.

New Research: Some studies suggest repeated steroids might accelerate cartilage degeneration, challenging their use in osteoarthritis